Prototyping generative approaches with Claude-Light

Lauren Smith

Aug 4, 2025

Source: John Kitchin

Machine learning and automation have the potential to transform scientific research, yet more data is needed to continue their trajectory. Self-driving laboratories, also called remotely-operated autonomous labs, are one approach to generating that data. They are expensive to set up and operate, however, and it is difficult for researchers to learn how to use these complex facilities.

To teach the skills researchers need, John Kitchin built Claude-Light. It's an inexpensive, remotely accessible instrument that can help researchers learn to intersect high-throughput experimentation and machine learning. "Claude-Light lowers the barrier for students and researchers to prototype and test automation and AI-driven experimentation before scaling to full self-driving laboratories," says Kitchin, professor of chemical engineering.

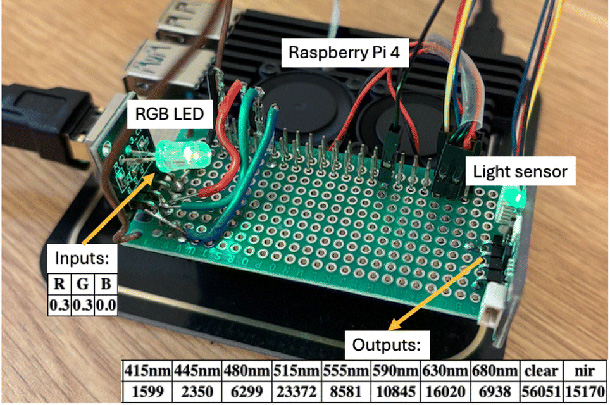

Claude-Light has three inputs: the red (R), green (G), and blue (B) levels of an LED. It can measure ten outputs: eight wavelengths of light, near infrared radiation, and total light. One of the newest features that makes Claude-Light even easier to use is a local server that Kitchin built to connect it to the desktop version of Claude, the large language model (LLM) from Anthropic. The similarity in names is coincidental. Kitchin chose the "Claude" part of Claude-Light as a phonetic play on "cloud." His recent experiments use the Claude Desktop app because it is easy to plug in the type of server needed to integrate Claude-Light.

With the integration, a user can remotely run an experiment on Claude-Light with natural language. The Claude Desktop user interface puts together all the functions and tools of Claude-Light, from generating data to fitting and plotting a line through the data.

Running Claude-Light from Claude presents opportunities to expand the capability of the LLM desktop. To explore these ideas, Kitchin is leveraging his expertise in design of experiments and his earlier work building pycse, a Python library for scientific programming. He has demonstrated a proof of concept for using an LLM to call tools and run external instruments from a natural language prompt.

Claude-Light is not only a real system that makes real measurements but also a proxy for other systems with input variables and outputs. This makes it particularly useful for prototyping automation programs and algorithms. "Students and researchers can use it to explore automation at multiple levels, from basic programming and experimental design to machine learning-driven optimization," says Kitchin.

Students and researchers can use Claude-Light to explore automation at multiple levels.

John Kitchin, Professor, Chemical Engineering

Kitchin's recent work documents Claude-Light's applications as a learning tool. In APL Machine Learning, Kitchin uses Claude-Light to illustrate some of the opportunities and challenges that LLMs bring to lab automation. He demonstrates a variety of approaches to automating a remotely-accessible instrument, starting with conventional programming tools and progressing to more advanced active learning methods.

In order to use these approaches, researchers need to know which design of experiments and algorithms to use for their specific research question, as well as how to code. "Not many scientists or engineers have all the skills required at the depth needed to do this," says Kitchin. He sees potential for LLMs to bridge gaps in these skills, specifically for instrument selection, structured data outputs, function calling, and code generation.

Relying on LLMs instead of traditional approaches to automation will require new ways of thinking. "Rather than learning specific syntax for code, we now have to learn how to prompt the models so they work the way we want," says Kitchin.

The potential to run automation through natural language is alluring, yet there are concerns about reproducibility, security, and reliability when using LLMs. "We always take risks in science. The point is to think critically about what these risks are, how likely they are, and what the consequences of them are. Then, develop risk mitigation strategies that are appropriate," says Kitchin.

Inverse problems are another area where Kitchin sees promise for generative models to reshape traditional approaches. Particularly challenging, inverse problems are used to find the input values that produce a desired output. Across disciplines, many problems can be framed as inverse problems, and generative approaches may offer new insights.

Source: John Kitchin, DOI: 10.1039/D5DD00137D

An image of Claude-Light showing the RGB LED that is controlled by the input settings (R, G, and B), and typical outputs from the light sensor.

Kitchin wanted to explore how generative artificial intelligence (AI) models can be used to solve inverse problems, so he used Claude-Light to generate data for a simple problem: how to set Claude-Light's LEDs to get particular values at specific wavelengths of light. Kitchin notes that real systems have nonlinearities and other complications, like one-to-many mappings, that are not in the Claude-Light dataset he generated for this exercise.

In Digital Discovery, he compares two generative AI methods for solving an inverse problem with two conventional approaches. The results for all four approaches were approximately the same, demonstrating that generative AI models can accurately and flexibly solve inverse problems.

"Claude-Light is enabling a lot of exploratory development," says Kitchin, who is extending his work with Claude-Light and generative models to nonlinear models, one-to-many mappings, and hidden variables.

For media inquiries, please contact Lauren Smith at lsmith2@andrew.cmu.edu.